Can one musical recording change a person's life? Hard as it may be to conceive of now, there was a time when many of us believed music could change the world for the better and have a positive effect on individual lives. There were particular recordings that had significant influence on each of us.

In December, 1969, I was a 17-year old senior at Suffolk High School. My friend Whitney Saunders came home from Woodberry Forest for the holidays toting a stash of new albums he'd acquired during the fall term. Whenever he came home, he turned me on to music I hadn't yet discovered---He went to a boarding school near the university town of Charlottesville; I lived in a musically insulated small town on the outskirts of what we then called "Tidewater."

Among this batch of records was something he thought I'd really like---an album called Stand Up by a band named Jethro Tull. Jethro wasn't a member of the band, just the name of the band (and an 18th century farmer/inventor). What made this British group stand out from all the others was the flute playing of the leader, Ian Anderson. Whitney was certain I'd enjoy this one.

Stand Up was cool---even the album cover was cool. The cover photo was a woodcarving of the band, the back showed a woodcut of the quartet walking away. When you opened the cover, the four band members actually stood up, just like a pop-up children's book.

Hearing the music was even cooler. I'd never heard anything like it. The ten songs roamed over a wide stylistic range---blues on the opener, "A New Day Yesterday;" folkie balalaika on "Fat Man" and "Jeffrey Goes to Leicester Square;" a jazzy spin through the classical "Bouree" (Bach, though I didn't realize it at the time); the jazz/rock fusion of "Nothing Is Easy." There were the pretty ballads, "Look Into the Sun" and "Reasons For Waiting," and dynamically diverse hard rockers, "Back to the Family," "We Used to Know" and "For a Thousand Mothers." The lyrics appeared to make sense, mostly, and I could relate to them.

What would have the biggest impact on my life, though, was the aggressive fluting of Ian Anderson. Up to that moment, I'd thought of the flute as an instrument for girls. There were no male flutists in the high school band. The flute produced a light, airy, high-pitched tone. And there wasn't much flute in rock or pop music. There was the occasional flute solo in a song by the Association or Mamas and Papas, and there'd been some nice flutework on Blood, Sweat & Tears' landmark second album earlier that year. Still, the flute was hardly an essential element in a rock band.

Ian Anderson, however, produced a different sound. He overblew, grunted, inhaled noisily and often hummed along with himself. This was new to me, though I'd later learn he picked up his style from the records of jazzman Rahsaan Roland Kirk.

The day after Christmas, I went down to the Band Box and bought my own copy of Stand Up. I played it over and over, dissected it, reviewed it for our high school newspaper, The Peanut Picker. I began whistling the flute parts, imagining myself as a flutist.

Shortly thereafter, I heard Herbie Mann's Memphis Underground on the new "underground" FM station, WOWI. A different, fuller, brighter tone, but just as assertive, intoxicating, amazing. That was it. I was hooked. I had to learn to play the flute!

I bought a flute from a former girlfriend in the high school band, Angel Ellis, for $25.00. She also gave me her fingering chart showing which keys to push to make different notes. I began teaching myself to play. At first, I nearly passed out, hyperventilating as I tried to get an approximation of the sounds I'd heard. But I was determined to sound like my new idols, Ian Anderson and Herbie Mann.

I discovered an earlier, jazzier Tull album, This Was, which included a version of Kirk's "Serenade to a Cuckoo." Then in April, 1970, a new Jethro Tull album appeared. Entitled Benefit, it featured a picture of Ian Anderson playing the flute while standing on one leg like a kilted flamingo, eyes bugged out at the microphone. A loud blast of heavy rock, Benefit blended the blazing electric guitars of Martin Lancelot Barre with Anderson's acoustic guitar and flute to create a unique sound. The record buying public began to take notice.

I spent the summer of 1970 practicing, practicing, practicing. In September, I entered Virginia Tech. My friend Hugh Spain called me from Randolph-Macon to tell me Jethro Tull was coming to Richmond on the first of November. The concert was scheduled for a Sunday night at the Mosque, and he had gotten some tickets for the front row of the balcony.

My hitchhiking buddy, Jimmy Coppola, and I thumbed from Blacksburg to Richmond on Friday night, October 30, 1970. We got as far as an all-night drugstore on the southside of Richmond, about an hour from Ashland where Hugh was awaiting our call. It was after midnight, and the only folks in the drugstore were a few members of the local late-night intelligentsia. They took one look at our long hair, and started the stereotypical comments of the time: "Hey baby." "Man, those are some ugly girls." Etc.

Facing an hour or more with these gentlemen of south Richmond, Jimmy and I immediately slipped into our best approximation of redneckia, and proceeded to have an enlightening conversation with our new-found friends. By the time Hugh arrived to pick us up, the local guys were inviting us to come back any time. Whew!

That Sunday night is a night I'll always remember. I'd been to a few concerts, even seen Led Zeppelin (they were terrible), but THIS was JETHRO TULL!! I was not disappointed. Ian Anderson was quite the showman, as the rest of the world would soon learn, and had already perfected many of the personalized rockstar moves for which he'd become known. He stood on one foot a la the Benefit album cover, danced like a crazed marionette, and directed the proceedings like some wild-eyed maestro in a thrift-store bathrobe. The flutework was intense, the band was hot. I was inspired.

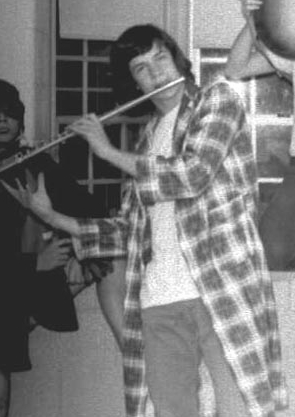

After the concert, we hitchhiked through the night back across the state, catching a ride most of the way with a bunch of fellow Tull fans in a VW microbus. I had now seen Ian Anderson in person, and I now had a role model for my own performing moves. I paradiddled my way through the dorm, flaunted my flauting, and got the look and the moves down pat.

After the concert, we hitchhiked through the night back across the state, catching a ride most of the way with a bunch of fellow Tull fans in a VW microbus. I had now seen Ian Anderson in person, and I now had a role model for my own performing moves. I paradiddled my way through the dorm, flaunted my flauting, and got the look and the moves down pat.

After Aqualung came out in the spring of 1971, Jethro Tull never looked back. I didn't think Aqualung was as good as the band's earlier work, but it certainly vaulted them into the superstar strata.

I continued working on my flute playing, practicing, listening to any flutist I could find. I played my flute in several bands in college, at anti-war demonstrations and panty raids, and pied-pipered my way through Virginia Tech. A note-for-note rendition of "Bouree" was always sure to get a "Wow, man, you're great" response.

Even today, playing jazz around Hampton Roads, I am often asked, "Do you play any Tull, man?" Sure. What would you like to hear?

copyright © 2002 Jim Newsom. All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission.

"Living in the Present"

-An Interview with Ian Anderson-